Slow adventure experiences, such as canoeing, stargazing or foraging, are characterised by a slower passage of time, immersion in the natural world and a sense of belonging to small social groups. During slow adventures, the perceptions of time, meaningful moments and a sense of togetherness are choreographed by adventure guides to shape tourists’ wellbeing through immersive experiences, ultimately helping them to re-establish a much-yearned-for connection with nature.

The contemporary world has become more mobile, interconnected and fluid, and, despite the expectation that technological change would increase people’s free time, the pace of life has only accelerated. People’s free time has been devalued, quality of life has been diminished and physical and psychological health has become one of the major concerns. To address this, prescriptions to take short, restorative trips into areas rich in nature have become a leading trend in public health programmes worldwide.

In the past several decades, the tourism industry has made attempts to promote responsible and sustainable travel through development of niche products based on nature, such as ecotourism, adventure tourism or wellness tourism. At the same time, people’s wellbeing has come into focus. Thus, immersive tourism activities in natural environments far from urban centres, such as nature reserves and national parks, are claimed to espouse preventative approaches to health.

Pulling people to less trafficked, healthier and greener destinations, and slowing down their activities, have become a new ethical consumer trend. The concept of slowness maintains its focus on learning how to value and cultivate a sense of time. Slow tourism celebrates simple, organic, local, traditional, affective and emotional dimensions of the experiences gained through immersion in the destination and local way of life. Slowing down has been adopted in tourism through developing experiences in remote, rural or natural spaces, as they can offer the qualities that many modern tourists seek, particularly focusing on extending time to savour the outdoor experience.

Slow adventure is one of the emergent trends in nature-based and peripheral tourism that responds to the call for sustainable development. The aim of slow adventure is to introduce consumers to the simplicity of just ‘being’ in the outdoors – in responsible and ethical ways. In the slow adventure context, undertaking activities is not constrained by time but rather conditioned by natural rhythms: changes of dark and light, fluctuations of the water’s surface, or the direction of the wind.

Consuming such experiences may lead to both hedonic and eudaimonic outcomes, and to the deepening and rounding of the outdoor experience. Slow adventure offers consumers the luxurious commodity of taking time to dwell in nature, being more mindful and developing a connection with their environment. It also allows space for disconnection from the stressful and disturbing stimuli by which the modern world is overly saturated. Slowing down and taking time to do activities may improve health and reduce anxieties, stress and depression, particularly in more affluent, digitalised and time-deprived societies.

The immersive entanglements with natural environs are generally augmented by a skilled guide. Allowing an expert to guide clients through an alien environment, enabling people to enjoy the haptic, olfactory, auditory or visual phenomena – be it the sound of splashing waves, the explosion of colours in the golden hour or the crackling of the campfire – may, briefly restore tourists’ peace of mind.

In uncertain times after Covid-19, being slow and mindful might alleviate some of the people’s anxieties and fears. In slow adventure environments, guides can foster longed-for feelings of reconnection, restoration, reunion or regeneration, and make a modest, but a meaningful contribution to the psychological wellbeing of the troubled inhabitants of the 21st century.

This is an abridged version of an article written by Jelena Farkić, whose inspirational blog can be accessed here.

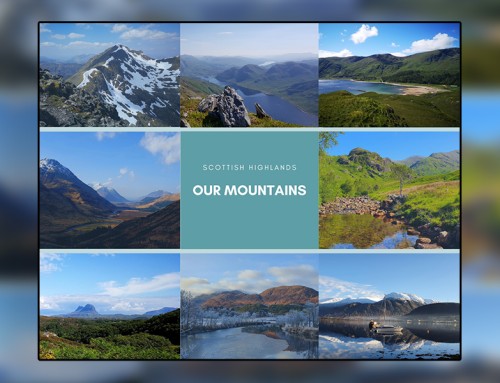

*Photo credit –

© Rupert Shanks, Wilderness Scotland